‘No crap beats’ – if that wasn’t on Keith Leblanc’s business card, it should have been.

‘No crap beats’ – if that wasn’t on Keith Leblanc’s business card, it should have been.

The man could just sit down at any kit – or program any drum machine – and make it sound rich and swinging, whether he was playing with Tackhead, Seal, Tina Turner, Nine Inch Nails, Depeche Mode, Bomb The Bass, ABC, Sugarhill Gang, Annie Lennox, Mark Stewart or Little Axe.

LeBlanc – who died in April – has to go down as a true beat innovator, embracing and developing drum technology and particularly developing a human/machine interface which always grooved beautifully and didn’t distract from the music.

Along with other key ’80s/’90s drummers Dennis Chambers, Jonathan Moffett, Ricky Wellman and Lenny White, he also had a killer right foot.

He grew up in Bristol, Connecticut, and was inspired to pick up the drum sticks after seeing The Beatles on TV. He was later influenced by what he called ‘pop’ music – James Brown, Cameo, Muscle Shoals, Gap Band, Parliament/Funkadelic – and became the house drummer for Sugar Hill Records in late 1979 and co-founder of grounbreaking funk/industrial/dub/rock outfit Tackhead alongside Skip McDonald, Doug Wimbish and Adrian Sherwood.

LeBlanc also recorded many solo albums, the best of which is probably Time Traveller, and played excellent live jazz/rock with Nikki Yeoh, Jonas Hellborg and Mano Ventura.

It’s sad to think one will never again hear that amazing LeBlanc/Wimbish bass and drums hook-up. Anyone who saw Mark Stewart, Little Axe or Tackhead live will remember how the first few minutes of every gig was usually just the two of them playing together. That lasted right through to the 2021 On-U Records anniversary shindig, though a masked Keith looked very frail.

movingtheriver had the pleasure of interviewing LeBlanc in 2010 for Jazz FM, and revisiting my notebook I found lots of interesting quotes I didn’t use in my original article:

On Sugarhill Records/co-owner Sylvia Robinson:

Sylvia was looking for Skip and Doug but they initially said no because they’d had a bad experience before. I was new to the band but I heard the words ‘recording studio’ and ‘money’ and bugged them until they said yes. The first Sugarhill Gang album was recorded in the Robinsons’ studio (H&L in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, down the road from Rudy Van Gelder’s famous studio) which was falling to bits! We’d cut a track on the Friday, drive home to Connecticut and hear it on the radio on the Monday. The whole industry was shaken up when rap started. It took them four years to catch up. But if the Robinsons had done 25% of the right thing, Sugar Hill Records would still be going. They screwed up. It was hard to watch the artists get ripped off and then watch those people flaunt money in front of them. We tried not to write anything because we knew how they were.

On playing live in the studio:

The first rap drummer was a white guy! Back then, playing live in the studio was normal. The arranger Jiggs Chase would get with the rappers, do an arrangement based on what they wanted to use and then give us charts. And then we’d add things. The musical ethic was really good at that time. You had to get it right or there’d be someone else in there recording the next day.

On hip-hop and drum machines:

After ‘Planet Rock’, anyone could make a rap record in their bedroom. When drum machines came out, I saw my job opportunities flying out of the window. They opened the door for everybody to do it. Then it dawned on me what I could program one of those better than any engineer. I did ‘No Sell Out’ just to see what I could do with drum machines.

On George Clinton/P-Funk:

I was offered the gig with Parliament – I asked Bernie Worrell if I should do it and he said, ‘Only if you want to chase the money all night!’

On his imitators:

The Red Hot Chili Peppers ripped us off, especially in the beat department. The drummer was checkin’ me hard!

On Prince:

Prince sabotaged my drum machine at First Avenue in Minneapolis. I was playing along and then the machine stopped and I heard this voice hissing through the monitor: ‘What’s the matter, can’t you keep time?’!

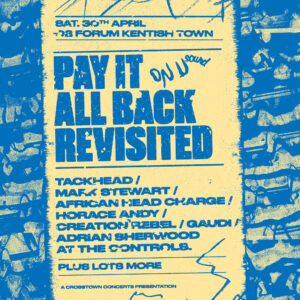

This was a twice-rescheduled London gig, initially designed to celebrate the 40th anniversary of On-U Sound Records.

This was a twice-rescheduled London gig, initially designed to celebrate the 40th anniversary of On-U Sound Records.