Lewis Taylor has never troubled the BRIT, MOBO or Grammy awards and never had a top 40 single or album but may be the most musically talented British solo artist of the last 30 years.

Lewis Taylor has never troubled the BRIT, MOBO or Grammy awards and never had a top 40 single or album but may be the most musically talented British solo artist of the last 30 years.

Over six studio albums – including last year’s unexpected NUMB, his first record for 18 years – Taylor’s work has embraced neo-soul, old-school R’n’B, prog, psych and yacht rock, influenced legions of blue-eyed-soul wannabes and been publicly lauded by David Bowie, Aaliyah, Paul Weller, Amy Winehouse, Leon Ware, Elton John, D’Angelo and Daryl Hall.

His classic self-titled debut album dropped on Island Records in 1996 and stunned the musical cognescenti. Who was this guy from Barnet who sung a bit like Marvin, played guitar like Ernie Isley, bass like James Jamerson and keyboards like Billy Preston, and created his extraordinary angst-ridden compositions in a North London flat on two digital reel-to-reel tape machines?

His second album – 2000’s Lewis II – was possibly even better, but sadly there were various reasons for its lack of commercial success. Lewis parted company with Island and recorded two further studio albums in the 2000s, Stoned Parts 1 and Part 2, and also issued The Lost Album and Limited Edition 2004. But what most fans didn’t know was that Lewis had a ‘secret’ 1980s history as purveyor of weird psychedelic pop/rock under the name Sheriff Jack and also as a touring guitarist in The Edgar Broughton Band.

It all adds up to a truly singular career, and Lewis is one of the most gifted artists working in music today. movingtheriver caught up with him as his new album NUMB was being released to rave reviews.

MTR: I gather you grew up in North London and were somewhat of a piano and guitar prodigy – can you tell me about your early experiences of seeing live music in the capital? Who would have been some artists you saw live/listened to?

LT: Ooh no, I wouldn’t say I was anything near a prodigy. My Dad was a wannabe musician who’d played percussion in a couple of jazz bands – Bongo Bernie they used to call him – so the real interest in music sort of came from being around him and I became obsessed with records. As a result live music has never interested me and it still doesn’t really, it’s all about the records. My dad liked a lot of big-band jazz – Stan Kenton was a fave of his, and he liked Latin stuff like Tito Puente. I also remember an album of Maya Angelou songs he liked as well cos it was sort of dark calypso. That was his thing – he liked anything that had that sort of exotic, syncopated rhythmic thing going on, but he liked some pop of the day too. He loved Mungo Jerry’s ‘In The Summertime’, it used to make him laugh, and I can remember him in the car singing along to the end choruses of TRex’s ‘Hot Love’. He was quite a strange man.

On the keyboards side, would you say you were ‘classically’ trained? I only ask because I hear little bits of ‘classical’ harmony on some of your stuff, like ‘Satisfied’ and ‘The Final Hour’.

I would say I had a bit of classical training. But because the guitar had taken over I’d stopped paying attention to my piano lessons, but some of it must have still seeped through so I do have a good grasp of music theory, but I still can’t read music. I used to cheat in my lessons. I would learn whatever piece I was given to learn by ear and pretend I was reading it. Because I had a precocious taste in rock music as a pre-teen, the fact that the lessons were all based around classical piano music only served to distance me from it even more. So it very quickly started to feel like an extension of school. I did eventually manage to splutter out: ‘Mum, I hate this – I’m only doing it cos you told me to’, and that was the end of it.

Which guitarists/bassists/keys players do you/did you idolise? Re. the former, I hear Ernie Isley, Eddie Hazel, maybe Richie Blackmore, and I detect a John McLaughlin influence too?

One of my biggest bass influences is Chris Squire. I first heard Yessongs in 1975 and all I could hear was this clicky-clang of his bass but he would also be going places melodically where someone like James Jamerson went and the combination was so unusual and inspiring. On guitar, Pete Townshend, just for his rhythmic thing he has going on, I definitely got my strong right-hand attack from listening to him. For soloing, yeah a bit of Blackmore, but when I really started trying to play lead Van Halen had just come out so apart from the finger-tapping aspect which I’m not really into, the way he interpreted the blues scale influenced me a hell of a lot. Michael Schenker was another one. And of course Jimi. I do like players like John McLaughlin and John Scofield, Allan Holdsworth as well, but I’m not lofty enough to go there!

Tell me about joining/touring with the Edgar Broughton Band.

It was a weird coincidental thing, one of the albums I’d borrowed from my cousin was an Edgar Broughton Band album so I’d first heard of them when I was 9 or 10. Ten years later my brother had got a job working at Steve Broughton’s studio. When Steve told him they were going to reform and were looking for a guitarist, he said: ‘Get my brother in, he already knows all your stuff’ so it went from there. I loved it. The dysfunctionality of their music and of the band itself sat very well with my own dysfunction! We toured round Germany, Switzerland and particularly Norway a lot, we played a huge stadium in East Berlin three years before the wall came down. Every tour was an experience of some kind, not always good, but even that was good! The one which really shone for me was an outdoor festival on a Norwegian island called Karlsoy. We played at midnight but it was daylight, really strange daylight. I’ll always remember the walk down to the stage and turning round to see this wonderfully eerie vision of Edgar waking behind me, his Lennon shades on, his long white mane of hair and this really odd, cold light from the midnight sun shining behind him. We played a blazing set that night. Love Edgar, love those guys!

Sheriff Jack – what are you memories of that period?

Steve Burgess was a bit of a character who had a shop in Crouch End called English Weather. He saw himself as a sort of record-shop guru and I suppose he was, to me at least, the imploding 19-year-old I was back then. It coincided with the Paisley Underground thing that was starting at the time so his shop specialised in that along with 60’s garage and psychedelia, and so I quickly became a regular customer there and we became friends. He’d also been involved somehow with The Soft Boys and Robyn Hitchcock and I went through a period of listening to them quite a bit. I probably misread a lot of what Hitchcock was doing as just silly nonsense and tried to do the same thing with the Sheriff Jack stuff. The name came from a track on a Red Krayola album called God Bless The Red Krayola And All Who Sail With It. Again, a very bizarre album to some that seemed to make perfect sense to me. On this song I think they’d deliberately recorded the drums without being able to hear the song so they would go out in and out of time with the rest of the music. I used to play that track over and over on so I thought it was fitting to name myself after that song. I wasn’t serious or ambitious about it and I’m still not quite sure why I did it to be honest, but I did.

When signing with Island, did you have any direct dealings with Chris Blackwell?

No I never met him. I wouldn’t be surprised if he didn’t even know I was signed to his label, let alone who I was!

Is it true that you worked quite a lot on that first Island album at their studios in St Peter’s Square, Hammersmith, with more of a ‘band’ vibe, before recording the album essentially by yourself?

Not really, no. I was still trying to find a direction and hadn’t found it at that point. So there was a lot of early material that was fairly dodgy. I’d gone in there with the multi-tracks to overdub a drummer to get a live feel. But even then everything else had been done at home. I used to have some bad habits – I would sometimes record the effects onto tape as opposed to sending the tracks to effects during the mixing stage, so I would just use a reverb unit, then compress the reverb so it really sort of sucked in, then record it with the dry signal. The album was actually mixed at that studio though, so I’m sure the notorious echo chamber is on there somewhere.

What was it like appearing on ‘The National Lottery’ show? And ‘Later…With Jools’? Did you enjoy that aspect of promotion?

Some of it I did, yeah. I actually was on ‘Later’ three times you know – oh yes. Once as Lewis, once on keys with Finley Quaye, and once as keyboardist with some rappers called Spooks.

Do you ever wonder how different your life would have been if ‘Lucky’ had been a big hit? (and btw, I’m stunned that ‘Whoever’ didn’t even chart – that sounds like a hit to me, even today…).

Oh thanks. I actually have a pretty good idea how I would have turned out had I been more successful – I’ve always had a few loose screws at the best of times but a successful career in music, and particularly the fame aspect of it, would’ve turned me into a complete basket case!

Is it true that it was completely your decision to scrap the second album for Island, before starting over and recording Lewis II? I do recall a comment at the Hanover Grand gig where you alluded to Island being responsible…

Not exactly, I pushed in such an extreme direction the other way with what eventually became The Lost Album, it was a knee-jerk reaction to a perceived ‘trapped in R&B’ feeling I was going through at the time and some people around me were in favour of it and others weren’t. In the end I think I lost confidence in it and did Lewis II instead.

It is mystifying to me why no singles were released from Lewis II. Do you regret that ‘You Make Me Wanna’ wasn’t released as a single? I might have gone for ‘My Aching Heart’ too…

I don’t know. I think things were fairly fragmented by then and really my heart wasn’t in it anymore, but I wasn’t aware of that so I was sort of on autopilot. Also a lot of the people who were at Island when I signed with them had left so a few things definitely sort of contributed to the way things went there.

That Hanover Grand gig around that time felt so positive and it was a thrill seeing an English artist making such patently world-class music, and starting with ‘Track’… Do you feel that that momentum wasn’t maintained? And how much do you lay at Island’s door?

Hmm, not much really, but I did at the time. In hindsight I don’t think I would have been an easy artist to work with, I was a guy who sounded like that but looked like this and I wouldn’t play ‘the game’. I’m surprised that they were as supportive as they were! I do remember it being a pretty good gig though.

Amy Winehouse was quoted as saying she wanted to work with Paul Staveley O’Duffy only because he’d worked with you – did you know Amy? Did she seek you out? She was obviously a big fan. I thought ‘Take The Box’ had more than a bit of your influence.

No, I didn’t know Amy and I wasn’t aware that she was a fan. She was a great singer though. Very sad what happened.

Did you record a whole Trout Mask Replica covers album? I remember hearing ‘Ella Guru’ and being knocked out by it.

Oh cool, I’m glad you liked that! No I didn’t do the whole album, it was a bit of an anal job. You can’t learn those songs that easily cos there isn’t a straight line going through them, well there is but it’s very, very bent. So the only way was to get the instrumental version of each song, record it onto a stereo track cos Beefheart always had two guitars panned hard left and right, then I would just drop in and overdub it phrase by phrase, erase the original then try and sing on it. I gave up after 13 tracks, couldn’t be bothered! LOL…

How do you feel Universal have treated your Island catalogue since you left the company? Do such things bother you?

No, not really. It’s a shame that they didn’t contact me when they did the expanded reissue thing but other than that it’s all cool.

Did you know beforehand that the 2006 Bowery Ballroom gig in NYC was going to be your last for a long while?

No I didn’t as such, but I had started looking at myself from a personal point of view by then and I was trying to figure out where I ended and where the musician began. Unfortunately that process coincided with the involvement of the US guys so I was on a different page to them and it was the wrong page to be doing what I was doing. I didn’t have a clue about that at the time though so my behaviour may have been a bit baffling to them!

Famously you withdrew much of your online presence in 2006 – what has driven you to ‘switch it on’ again? And how do you feel about being a solo artist now with all the social media marketing etc. that goes along with it?

I dunno really, up until about two years ago I still wasn’t bothered, if somebody told me I’d be putting an album out in 2022 I’d have laughed at them. It feels a bit like it came out of nowhere but at the same time it doesn’t feel like one of those ‘I just have to create again and now is the time’ scenarios either. There was always a part of me that was pretty cynical about that way of thinking, and coming back to it now I still think like that, but in less of a cynical way if that makes any sense. The whole social media thing is just another thing – ‘new skin for the old ceremony’ – it has its pros and cons just like everything else that came before it.

You used to make music using a digital reel-to-reel tape machine in your home – is that still the case?

No, it’s all on a Mac now.

What do you think of the streaming revolution and its effect on album listening? Do you miss the physical product (and is NUMB going to appear on vinyl?)

I don’t really miss the physical format, I actually like mp3s, I like the convenience of them. Yes NUMB is definitely getting a vinyl release some time next year. Be With Records are doing it, the guys who did the vinyl of the first album. I’ve heard the test pressing and it sounds great.

B-sides – you created some brilliant music. Personal favourites: ‘Lewis III’, ‘Pie In Electric Sky/If I Lay Down’, ‘Asleep When You Come’. Is there anything more in the vaults? What’s the favourite of your B-sides?

Oh cool, thanks! No I don’t think there is anything left over, each set of B-sides was written and recorded specifically for each ‘single’ release. My favourite has always been’ I Dream The Better Dream’. In my fantasy it’s what early Soft Machine would’ve sounded like if Marvin Gaye was their lead singer.

I enjoyed your collaborations with Deborah Bond and The Vicar’s ‘The Girl With Sunshine’ (please tell me more about that). Did you consider any other duets/collaborations in a similar vein just before your ‘retirement’? Or is there anything in the pipeline for the future?

Both of those things were done at a time when I was starting to back away and shut up shop so it was all done via email. The Deborah Bond thing was a nice little job, cute little song. The Vicar thing was a guy called David Singleton who was somehow attached to Robert Fripp, I’m not sure exactly how. I think he’d heard a tune from The Lost Album which was featured on a compilation that came free with one the mags and so he sent an email asking if I’d like to sing on this funny album he was doing. Why did I do it? Good question. Looking back I think I was probably just flattered that someone was still interested at that stage.

You were involved as a ‘sideman’ capacity with Gnarls Barkley and Finley Quaye – was there ever any possibility of you just becoming an ‘anonymous’ sideman post-2006? Could you have carried on as a session player?

No I don’t think so. I definitely needed a total break from everything. I was approached with a couple more MD jobs after the Gnarls thing but as soon as I started thinking about the possibility of doing them it just felt wrong. I did reconnect with The Edgar Broughton Band though and we did a few more tours over the course of about four years, but that doesn’t count cos they were mates and it was away from Lewis Taylor and the mainstream industry. We toured the same places as they had always done, Norway, Germany and Switzerland. I think a few gigs were recorded but not for a record, although we did do a German Rockpalast show which had a DVD and CD release, and there are a few fan-made clips of some Norway shows on YouTube.

Listening to NUMB, it’s striking how much lower your vocals are in the mix as opposed to say on Lewis II. There’s a ‘horn-like’ feel to your vocals now too. I gather you particularly love Johnny Hodges’ playing?

That’s interesting, it didn’t occur to me that I sounded like that! I do remember saying I liked Johnny Hodges but I love all the classic alto and tenor players. The Hodges reference was probably from when I was listening to a Charlie Parker Jam Session album and Johnny Hodges was one of the many players on it, and compared to everyone else’s blazing solos his playing was so small and sly in a wink-wink kind of way and I remember being very entertained by it at the time. But then I discovered Albert Ayler and everything changed.

Who’s that on backing vocals on ‘Apathy’? And are there are any other guest appearances on the album?

Well that’s Sabina (Smyth) of course! And she is by no means a guest, any female vocals you hear are her! She’s on all the albums. We write, produce and mix all the albums together – it’s all us.

Is that a Syd Barrett interview reference on ‘Feel So Good’? (‘I even think I ought to be’…)

Of course! God bless Syd. I love him.

‘Nearer’ is extremely complex. Any memories of how that tune came about?

It’s strange cos while it does sound complex it was actually one of those tracks the just seemed to write itself.

NUMB is generally downbeat but also uplifting, kind of a modern blues. A key theme seems to be having the courage to be yourself, faults and all, and the problems that go along with that. ‘Braveheart’ says it all.

That is a key theme, yes. Self-awareness and trying to be more authentic than you may have been in the past. All that shite. Yeah, I love ‘Braveheart’.

It’s a beautiful mixing and mastering job on NUMB. It’s really easy on the ear. Do you enjoy that aspect of music-making?

Thanks man. I think I enjoy that and the programming more than anything. Using a program like Logic is so much fun. You’re only limited by yourself. Logic will do anything you want it to and having those tools accessible is a great thing.

I think NUMB is really original (and, for what it’s worth, your best album since Lewis II…), but what music do you listen to for enjoyment now?

Thank you so much and I’m so glad you like it. I listen to a lot of opera these days. Totally away from anything I do as a musician.

How do you feel about people covering your stuff? Anything you particularly like? I’ve heard a few – Taylor Dayne, Peter Cox, Beverley Knight. Jarrod Lawson plays a great live version of ‘Right’. And of course Robbie. Presumably the latter has been absolutely vital for your income stream.

I think it’s cool and I think Robbie did a great job on ‘Lovelight’. I was watching some footage of him the other day and he’s such a powerhouse as a performer.

Do you miss playing live at all? Personally I found the last few years of your live stuff in the mid noughties a little ‘perfect’ with great players but maybe a little too slick… Do you agree? And any chance you might play live behind NUMB?

I actually thought that last band, myself, Ash Soan, Lee Pomeroy and Gary Sanctuary was the best band I ever had. I heard some tapes of us when we were over in NYC and we were so fierce.

Finally, how would you sum up your career in music thus far?

Hmm, probably with a small ‘c’…

Thank you, Lewis…

Further reading: An edited/updated version of this interview appears in the April 2023 issue of Record Collector magazine.

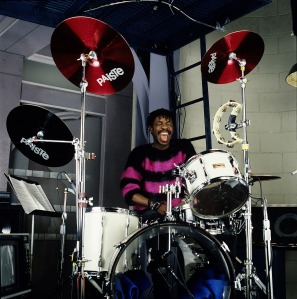

You toured Bebop (I was there at London’s Town & Country Club). Did you enjoy playing this stuff live? There was a rumour that the drummer (whose name escapes me) cost more than the rest of the band put together…

You toured Bebop (I was there at London’s Town & Country Club). Did you enjoy playing this stuff live? There was a rumour that the drummer (whose name escapes me) cost more than the rest of the band put together… There definitely seems to be something in the London air this summer.

There definitely seems to be something in the London air this summer.