Producer Steve Lillywhite recently named Phil Collins as the best drummer he’s ever worked with, pretty high praise considering Lillywhite has also shared studios with Simon Phillips, Carter Beauford, Mel Gaynor, Mark Brzezicki, Jerry Marotta and Stewart Copeland.

Producer Steve Lillywhite recently named Phil Collins as the best drummer he’s ever worked with, pretty high praise considering Lillywhite has also shared studios with Simon Phillips, Carter Beauford, Mel Gaynor, Mark Brzezicki, Jerry Marotta and Stewart Copeland.

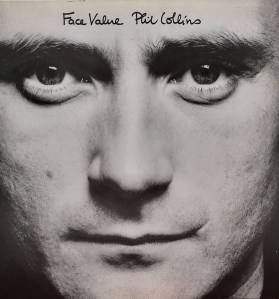

And Phil’s excellent drums were all over his seriously impressive (and very long for 1981, clocking in at over 47 minutes) debut solo album Face Value, released 45 years ago this month, and a record that has fascinated this writer since the age of eight.

But by 1981 Phil had nothing to prove from a drumming perspective. It was the quality of the material and arrangements that bowled people over. And yet Face Value is so much part of the furniture these days that it’s easy to forget just how expertly crafted it is.

Many of the album’s songs started life as primitive home demos, featuring rhythm box, piano and vocals, Collins having a lot of time on his hands after separating from his first wife (‘I Missed Again’ was originally a mid-tempo shuffle with the working title of ‘I Miss You Babe’).

A few other tracks were developed in the studio with various muso friends, including L Shankar on violin, Eric Clapton and ex-Weather Report bassist Alphonso Johnson, and then there were the two famous cover versions (or three if you count Phil’s almost-silent rendering of ‘Over The Rainbow’ at the end – the very first ‘secret’ track?).

The resulting material was an embarrassment of riches. Phil threw everything but the kitchen sink at Face Value: singer-songwriter balladry, Motown, Earth, Wind & Fire, jazz/rock, Beatles beats. Even a touch of Barry White (but no prog…). And all of it pretty much works.

He took full advantage of Townhouse Studios’ famous stone-clad drum room and the superb technical skills and easygoing manner of co-producer Hugh Padgham.

‘In The Air Tonight’ arguably changed the music business forever (as, arguably, did the cover – was this the first album that had the artist’s handwriting on the front?). Had there ever been a quieter album opener? Or UK #2 single (#19 in the States)?

Just a spectral Roland CR-78 rhythm box playing a loose approximation of Phil’s beat from Peter Gabriel’s ‘Intruder’ (and at exactly the same tempo) and a few synth chords (starting in D-minor, the saddest of all keys…). And then the massively compressed, mid-song fill is always louder than you think it’ll be.

In fact, compared to modern ‘pop’ music, the whole album has an enormous amount of space. Even the silence between each track (apart from the mid-record medley) seems unusually elongated and very deliberate, possibly because of the huge variety of musical styles.

Atlantic (Phil’s label in the US) boss Ahmet Ertegun said something interesting about ‘In The Air’: for years afterwards, it was always his go-to track for demonstrating a sure-fire hit – rather an extraordinary statement, when you think about it.

Phil was also becoming a more-than-useful pianist – check out his lovely voicings on ‘Hand In Hand’ and impressive rhythm playing (just the black keys!) on ‘Droned’.

The success of Face Value was a huge gamechanger for his Genesis colleagues. The ‘funny guy’ behind the kit who had always felt a bit like an outsider was now calling the shots. Newfound respect from Messrs. Rutherford and Banks. There would be no more drummer jokes.

The album revolutionised Virgin Records too. Its massive success (UK #1, US #7) was almost as seismic as Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells had been five years before, ushering in the label’s mega-selling pop era of Culture Club, Human League et al.

‘Phil and Peter Gabriel are delightful people. Nothing’s too much trouble for them and it’s also true that because they’d both bother to go into the office to see everyone, the staff would work their balls off for them.’ Richard Branson, 1999

If Phil’s solo career had only ever consisted of Face Value, his legacy would have been assured. (In fact many, including this writer, believe he hasn’t produced much solo stuff of worth since…)

(Postscript: my 1980s WEA CD sounds great but is apparently a bootleg, with a few funny misspellings inside the inlay card – ‘Sharokav’ on violin – and a weird Eric Clapton pseudonym: ‘Joe Partridge’…)

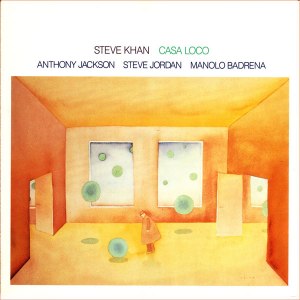

Continuing our look at some of the finest jazz/rock albums of the 1980s. You can find part 1

Continuing our look at some of the finest jazz/rock albums of the 1980s. You can find part 1  1980s jazz/rock generally gets the side-eye these days.

1980s jazz/rock generally gets the side-eye these days.

Bryan Ferry’s one and only UK #1 album to date (and biggest-selling record in the US) was released 40 years ago this month.

Bryan Ferry’s one and only UK #1 album to date (and biggest-selling record in the US) was released 40 years ago this month.  Fripp’s debut solo album, originally recorded at New York’s Hit Factory between January 1978 and January 1979, has endured endless tinkering from the artist including various remixes/reversions.

Fripp’s debut solo album, originally recorded at New York’s Hit Factory between January 1978 and January 1979, has endured endless tinkering from the artist including various remixes/reversions.