Marvin entered 1983 with mixed emotions.

His comeback album Midnight Love, released in October 1982, was a certified hit, with decent sales, good PR and an attendant single ‘Sexual Healing’ that was building up quite a Grammy buzz.

But there were plenty of other problems brewing: in his rather paranoid state, Marvin believed that pretenders to his throne like Teddy Pendergrass, Frankie Beverly (whom Marvin had mentored early in his career), Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson were cashing in on his style and sound. The latter had even taken to wearing aviator shades and ‘military’ garb.

Elsewhere, Marvin’s relationship with his father had hit a new low. Bitter and resentful, he considered physically ejecting Father from the family home but decided instead to stay away completely.

The other problem was cashflow. Marvin was spending so much money on ‘extras’ that he had been forced to give up his houses in Bel Air and Palm Springs. Despite all this, in the first few months of 1983, Marvin reminded the music world of his luminous genius and, against all the odds, provided a few career high-points.

Broke and entering an introspective period, he found himself spending quite a lot of time at his sister Sweetsie’s pad. It was there, on Saturday 12 February 1983, that he got together with chief musical collaborator Gordon Banks to cook up a version of the national anthem that he would sing the next day before the National Basketball Association’s All-Star Game.

Despite the last-minute planning, there was no margin for error: Marvin’s performance would be broadcast live on national TV. He not only pulled it off – he smashed it out of the park. Only Marvin could have come up something so singular. His huge respect for the athletes ensured that he raised his game accordingly.

Funky, spiritual, heartfelt and yet controversial, it was a triumphant reading of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’, and one of the highlights of his career.

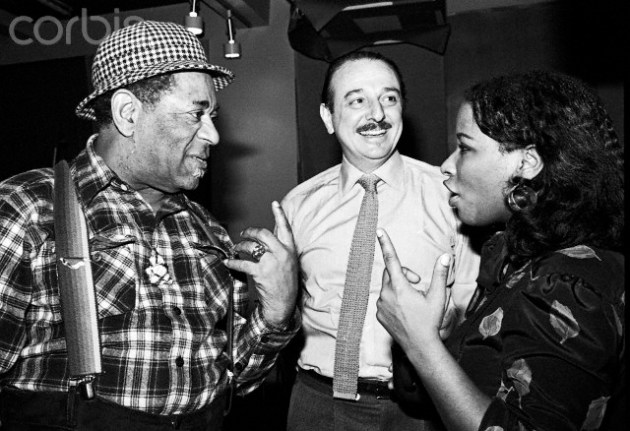

Less than two weeks later, on 23 February, there was another personal milestone for Marvin when he was awarded his first Grammy awards at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles.

That the Best Male Vocal and Best Instrumental Performance awards were ‘only’ in the R’n’B category scarcely mattered. He had moved out from behind his Grammy nemesis Lou Rawls’ shadow and finally gained the acceptance of his peers, something that was extremely important to him. His speeches were heartfelt and touching.

His performance of ‘Sexual Healing’ was not an unqualified success (it was 10 or 15 BPMs too slow and Marvin seemed slightly uncomfortable), but it’s still essential and moving stuff.

Another very happy moment happened a few months later when Marvin appeared with Gladys Knight and the Pips on another TV special. According to David Ritz’s classic book ‘Divided Soul‘, Marvin and Gladys argued backstage about whose version of ‘I Heard It Through The Grapevine’ to do. He finally deferred to her, but still turned in another joyous and brilliant performance.

Then, on 25 March 1983, the Pasadena Civic Auditorium hosted the ‘Motown 25’ anniversary concert, most famous for Michael Jackson’s spellbinding reading of ‘Billie Jean’. Marvin once again defied expectations and provided one of the highlights of the evening.

Though looking somewhat haggard, his blues/gospel piano playing and philosophical pronouncements on the value and history of black music were nothing less than captivating. His subsequent performance of ‘What’s Going On’ was perhaps perfunctory in comparison, but still essential viewing.

Tougher, tragic times were to come over the next year, but for a few months in early 1983, Marvin was seeing a lot of his professional dreams come true. No one could take that away from him.

Years before his huge hit ‘Ghostbusters’, Ray had played guitar on some great albums of the ’70s (Stevie’s Talking Book and Innervisions, Rufus/Chaka Khan’s Rags To Rufus, Harvey Mason’s Funk In A Mason Jar, Marvin’s I Want You, Leon Ware’s Musical Massage), not to mention sessions with the likes of Boz Scaggs, Barry White, Tina Turner, Herbie Hancock and Bill Withers.

Years before his huge hit ‘Ghostbusters’, Ray had played guitar on some great albums of the ’70s (Stevie’s Talking Book and Innervisions, Rufus/Chaka Khan’s Rags To Rufus, Harvey Mason’s Funk In A Mason Jar, Marvin’s I Want You, Leon Ware’s Musical Massage), not to mention sessions with the likes of Boz Scaggs, Barry White, Tina Turner, Herbie Hancock and Bill Withers.