Sly Stone

Anthony Jackson

Jack DeJohnette

Al Foster (drummer with Miles Davis/Sonny Rollins/Herbie Hancock etc.)

Chris Hill (DJ and member of the so-called ‘Funk Mafia’)

David ‘Syd’ Lawrence (cricketer)

Wayne Larkins (cricketer)

Bertrand Blier (film director/writer)

Dave Bargeron (trombonist with Jaco Pastorius Big Band, Carla Bley, George Russell, Steely Dan etc.)

Jamie Muir (King Crimson percussionist)

Alf Clausen (‘Moonlighting’/’Fame’/’Ferris Bueller’/’Naked Gun’ soundtrack composer)

Michal Urbaniak (violinist with Miles Davis/Lenny White/Jaco Pastorius etc.)

Antony Price (designer for Bryan Ferry, Robert Palmer, David Bowie etc.)

Luis Jardim (Seal/Annie Lennox/FGTH/Grace Jones/George Michael percussionist and, according to Steve Lipson, he also played bass on ‘Slave To The Rhythm’…)

Hermeto Pascoal

Damien Thomas (‘Twins Of Evil’/’Tenko’/’Shogun’/’Pirates’ actor and movingtheriver’s uncle)

Jellybean Johnson (drummer and guitarist with The Time/The Family/Janet Jackson etc.)

Nicky Katt (‘Dazed And Confused’/’Insomnia’ actor)

Roy Ayers

Tony Roberts (‘Annie Hall’/’Play It Again Sam’/’Hannah And Her Sisters’/’Serpico’ actor)

Andy Bey

Tony Slattery

Rob Reiner

Richard Darbyshire (Living In A Box co-founder/vocalist/songwriter)

Clem Burke

Chris Rea

Diane Keaton

Martin Parr (photographer)

Patricia Routledge

Sheila Jordan

Peter Jason (‘They Live’/’Prince Of Darkness’/’In The Mouth Of Madness’ actor)

Brigitte Bardot

Dave Ball (Soft Cell keyboardist/co-founder)

James Prime (keyboardist with Deacon Blue/John Martyn)

Robin Smith (cricketer)

Joan Plowright

Lalo Schifrin

Sly Stone

Rick Buckler (Jam drummer)

David Thomas (Pere Ubu frontman)

Sam Moore (Sam & Dave)

Mike Ratledge (Soft Machine co-founder)

Diane Ladd

Pauline Collins

Eddie Palmieri

D’Angelo

Biddy Baxter (‘Blue Peter’ editor)

Chuck Mangione

Steve Cropper

George Wendt (Norm in ‘Cheers’)

David Lynch

Gene Hackman

Brian Wilson

Andy Peebles (radio presenter and writer, the last Brit to interview John Lennon)

Terence Stamp

Chris Jasper (Isley-Jasper-Isley keyboardist/songwriter and solo artist)

Phil Upchurch

Alex Wheatle (writer, activist and London legend)

Roberta Flack

Prunella Scales

Claudia Cardinale

Marilyn Mazur (percussionst/vocalist with Miles Davis/Jan Garbarek/Wayne Shorter etc.)

Flaco Jimenez (accordionist with Ry Cooder/Bob Dylan)

Drew Zingg (guitarist with Donald Fagen/Boz Scaggs/David Sanborn/Marcus Miller)

Barry McIlheney (Smash Hits/Q/Empire writer)

Simon House (Bowie/Thomas Dolby/Japan/Hawkwind violinist)

Rick Derringer

Dill Katz (bassist with Barbara Thompson’s Paraphernalia/District Six/Ian Carr’s Nucleus)

Henry Jaglom (film director)

John Robertson (footballer)

Ed Williams (‘Ted Olson’ in ‘Police Squad’ and the ‘Naked Gun’ movies)

Harold ‘Dickie’ Bird (cricket umpire)

Roy Estrada (Little Feat/Mothers Of Invention bassist)

Wishing all movingtheriver.com readers a happy and healthy 2026, with loads of cash.

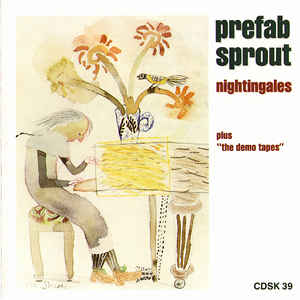

Prefab Sprout’s 1988 album From Langley Park To Memphis was their pop breakthrough, reaching #5 in the UK charts, and is probably most casual fans’ favourite.

Prefab Sprout’s 1988 album From Langley Park To Memphis was their pop breakthrough, reaching #5 in the UK charts, and is probably most casual fans’ favourite.