Art Blakey

Here’s another selection of choice quotes taken from various 1980s magazines, TV shows, biographies and anthologies that have drifted through my transom in the last few months.

Check out the first instalment here if you missed it.

‘Morrissey’s a precious, miserable bastard. He sings the same song every time he opens his mouth. At least I’ve got two songs: “Love Cats” and “Faith”.’

Robert Smith of The Cure, 1985

‘George Clinton told me how much he liked Around The World In A Day. You know how much more his words mean than those from some mamma-jamma wearing glasses and an alligator shirt behind a typewriter?’

Prince, 1985

‘It would be nice to meet Madonna and squeeze her bum.’

Level 42’s Mark King looks forward to his first US tour, 1986

‘I hope nobody bought houses.’

Slash/Warners executive Bob Biggs upon hearing a preview of Faith No More’s Angel Dust album (OK, this quote is from the early 1990s, but wtf…). The band had bought houses…

‘The musician is like a house, and the music is like a friend that’s always out there knocking on the door, wanting nothing more than to come in. But you’ve got to get your house in order for music to come in. That’s where discipline comes in.’

Robert Fripp, 1984

‘Like the first side. The second side is rubbish. Miles don’t play jazz no more but feels kind of funny about it, so instead of just admitting that his chops aren’t what they used to be, he puts jazz down.’

Branford Marsalis on Miles Davis’s Tutu, 1986

‘Remember the hits? “Labour Of Love” was inspired by Antonio Gramsci, a love song called “Violently” and a tale of kitchen-sink realism about wife battery called “Looking For Linda”. We heard those songs on Radio 1 back to back with Yazz and we’d piss ourselves laughing. We pulled off the trick three times and I always think that lyrically I can pull it off again.’

Hue & Cry’s Pat Kane remembers the good old days, 1995

‘I have to be myself, and if being in rock music forces me to pretend I am an idiot or that I have to wear tight trousers or a wig, then I have to get another job.’

Sting, 1988

‘I heard the title song (‘Storms’) on the radio and the drum sound still makes me want to cry. I love Glyn (Johns, producer) but there were times during that album when I went back to the hotel to cry.’

Nancy Griffith on her 1989 album Storms, 1991

‘I would say that my entire life has been one massive failure. Because I don’t have the tools or wherewithal to accomplish what I want to accomplish.’

Frank Zappa, 1986

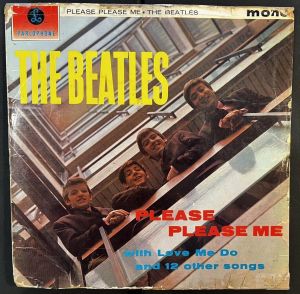

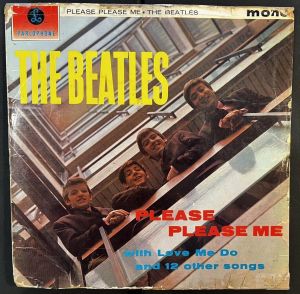

‘I went into the old EMI offices many times in the late ’80s and it never occurred to me to look up in reception and see exactly where that iconic photo had been taken. In the ’80s it seemed we had been looking forward.’

David Hepworth on the famous Beatles photo from the cover of Please Please Me

‘I tried the Jesus and Mary Chain but I just couldn’t believe it. It’s awful! It was so sophomoric – like the Velvets without Lou. I just know that they’re kids from Croydon! I just can’t buy it.’

David Bowie, 1987

‘I was surprised how hip it is. There’s a strange thing I don’t understand of people in Boy George outfits dancing to Jimmy McGriff and old Jackie McLean Blue Note records in discos.’

Guitarist John Scofield on the latest English ‘jazz revival’, 1988

‘Songwriting’s a craft, that’s all. I always knew my lyrics were better than anyone else’s anyway. I just edit more than other people, that’s my f***in’ secret. Also I never sleep and that helps too. You’ve got more time that way.’

Shane MacGowan, 1989

‘I hate having my picture taken, I always look like such a dog.’

Kirsty MacColl, 1989

‘I was a patsy. I never made more than $200 a week at the Five Spot.’

Ornette Coleman looks back on his legendary six-month residency during 1959 and 1960, 1985

‘All of us were naive, not just Ornette. We couldn’t even pay our rents. And they were making lots of money off us. That club was jammed every single night we were there.’

Charlie Haden on the same residency, 1985

‘You walk into the record label and they just weren’t as friendly as they used to be. When the record’s not a success, it’s your fault, and so you take on all those feelings. The label doesn’t sit down and talk to you. And they don’t drop you either, because they don’t want to lose you to the competition – just in case you do come up with something good next. And so they just remain sort of not as friendly, no more: “Hey Kevin, how are you?” It’s a head-f*ck, and you just have to work it out yourself.’

Kevin Rowland on the commercial failure of his 1988 solo album The Wanderer

‘Pop stars live the life of Caesar. And we know where the life of Caesar leads: it leads to blankness, it leads to despair. That’s the real message of these rock stars’ lives. To the public, they represent vitality, youth, innocence, joy. But in private life they represent despair and an infatuation with death.’

Albert Goldman, author of ‘The Lives Of John Lennon’ and ‘Elvis’, 1988

‘I remember sitting next to the stage and seeing all those little red lights glowing on the amps while we waited for the guys to come out and give us a real pasting.’

Allan Holdsworth reminisces about early gig-going, 1985

‘I have the best legs in the business. And they’ve got dancing feet at the bottom.’

David Lee Roth, 1982

‘There’s only one woman I have deep respect for in this industry and that’s Chrissie Hynde.’

Annie Lennox, 1986

‘I would have thought that people would be pleased to have a band that could play half decently.’

Francis Dunnery bemoans It Bites’ poor standing with the British music press, 1989

‘Sometimes he would call for Monk out of the clear blue sky. “Thelonious! Come save me from these dumb young motherf*ckers!”‘

Wynton Marsalis on playing with Art Blakey in the early 1980s

‘Prince really wants to be white. I know what that’s like. I tried hard to be white too.’

Daryl Hall, 1985

‘What we do is an alternative to Elton John and Chris Rea and all those old bastards who were there and still are. It’s embarrassing to see these old people like Dire Straits doddering about, they’re hideous.’

Robert Smith, 1989

‘I’ll tell you what I dig. In the Sting movie “Bring On The Night”, Omar Hakim taking off on that tune. Like Tony Williams, Jack DeJohnette. That’s being real free and comfortable. I don’t take my drums seriously, and they do.’

Drummer for the stars Jeff Porcaro, 1989

‘I believe that Bill (Bruford) and Adrian (Belew) thought that Beat was a better album than Discipline. I have no idea how anyone could come to that conclusion.’

Robert Fripp of King Crimson, 2022

‘Thanks for letting me drop by, guys. Hope I didn’t ruin your album.’

Herbie Hancock bids farewell to Simple Minds after playing a synth solo on their 1982 song ‘Hunter And The Hunted’

‘You should have seen us trying to sound like Windham Hill. We’d fall on our butts, man. I learned that you can’t fake it.’

’70s jazz/rock pioneer Larry Coryell on his mid-’80s collaboration with violinist Michal Urbaniak, 1985

‘We weren’t asked but we wouldn’t have done it anyway.’

Robert Smith on Live Aid, 1985

‘The band is getting back together and playing, maybe every six months or every year. If I can do so without it being public knowledge, that would be great. But I can’t do it, obviously. It would be nice to play together just as friends.’

Jimmy Page on Led Zeppelin reunions, 1986

‘I really, really would like to be in Led Zeppelin again. Whether or not time allows that to happen, I don’t know.’

Robert Plant on Led Zeppelin reunions, 1988

‘I’m a Catholic, and I would just ask God to to please help me find my own style. It’s not going to be like Tony or Elvin, so that when you hear me on a record, you know it’s Al Foster on the drums.’

Al Foster on his ‘stomping’ hi-hat technique, 1989

‘I feel I’ve created a field in which other people can discover themselves. I’m disappointed that they don’t create the room for me to discover myself.’

Robert Fripp on his King Crimson bandmates, 1984

‘I find therapy enormously valuable. It’s like car maintenance, send yourself in to be serviced every few thousand miles and, with any luck, it stops major problems developing.’

Peter Gabriel, 1989

‘I went to see this band INXS from Australia. They were on OK band, very much like a version of the Rolling Stones, but not as good. The singer is good and he looks great, but he doesn’t really move. He can’t be expending much energy.’

Mick Jagger, 1988

‘The band was like a fake democracy. Henley and I were making the decisions while at the same time trying to pacify and cajole the others.’

Glenn Frey looks back on The Eagles, 1988

‘(Jeff) Beck’s was a miserable f***ing band, horrible. Beck is a miserable old sod, but I do love him as a guitar player.’

Rod Stewart, 1988

‘I’ve always found it easier to write for other people. I feel terrible inhibited about writing for me. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve resigned myself into believing that I’m a moderately good singer.’

David Bowie, 1988

‘Of my writing partners since John (Lennon), Denny Laine was obviously nowhere near as good. Stevie Wonder is very good, but he’s not a lyricist. Michael Jackson is not as good of a writer as he is a performer. And Eric Stewart was good, but again, not as good as John.’

Paul McCartney, 1988

‘This new Clash compilation, which is meant to have sold a million copies, should be making me a rich man, but someone told me you only get quarter royalties for compilations. The CD wasn’t invented then so that wasn’t in the contract either. So I think I don’t get them royalties either. To tell the truth, I think we’re all a bit skint really.’

Joe Strummer on the legacy of The Clash, 1988

‘Those weird people on the street – every hundreth weirdest one has a Steely Dan record at home. That guy who hijacked a bus today probably has 47 copies of The Royal Scam.’

Walter Becker on Steely Dan’s audience, 1981

‘In 1981, something happened which changed my way of working with music. I woke up on a friend’s sofa in New York and simply understood something I’d known for a while: music was always present, completely with a life of its own, as a friend.’

Robert Fripp, 1984

‘The price of a ticket goes from two dollars to 20 dollars, the act doesn’t do an encore, someone has to stand in a long line, and it’s all my fault.’

Bill Graham on stadium rock, 1988

‘There are a lot of people who didn’t make a commitment and now they’re no longer with us. We lost Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson, Jimi Hendrix. I think maybe some of them didn’t know where or when to get off. The important thing is to be here.’

Al Green, 1988

‘Hell, we steal. We’re the robber barons of rock’n’roll.’

Donald Fagen of Steely Dan, 1981

‘After recording it, I flew off to see my manager and I said to him, “You’d better watch who you’re talking to. I’m the guy who wrote “Addicted To Love!”‘

Robert Palmer, 1988

‘I get the fans who write poetry. I have a slight David Sylvian audience, whereas Chris (Lowe) gets the sex audience, the ones who write obscene letters! It’s quite thrilling, actually!’

Neil Tennant of The Pet Shop Boys, 1988

‘It was the Enniskillen bombing that did it. The man whose daughter died beside him under the rubble; he was burning inside but he was so forgiving, so gracious. I thought, Christ, this is what courage is all about – Elton, just shut up and get back to work. After all, once you’ve been exposed naked on the cover of The Sun you ought to be able to face anything…’

Elton John on his 1988 comeback

‘It’s a better product than some others I could mention.’

David Bowie defends the Glass Spider Tour, 1987

‘Back then I thought I’d lost it and I did a bunch of things I was really unhappy with – all in public and on record. But it turned out not to be true. My ability hadn’t deserted me. And it won’t go away. Ever.’

Lou Reed, 1988

‘Michael Jackson’s just trying to cop my sh*t. I was insane years ago…’

Neil Young, 1988

‘I’ve said a lot of things in my time and 90 percent of them are bollocks.’

Paul Weller, 1988

‘We were excellent. Some of the best records of the ’80s are there. For the last six months of Wham!, it was OK to like us, we got a little hip. I cannot think of another band who got it together so much between the first and second albums. On Fantastic, you can tell I don’t think I’m a singer but some vocals on Make It Big are the best I’ve done. Even if we were wankers, you still had to listen.’

George Michael reassesses Wham!, 1998

‘The gig I have as the drummer in King Crimson is one of the few gigs in rock’n’roll where it’s even remotely possible to play anything in 17/16 and stay in a decent hotel.’

Bill Bruford, 1983

‘When I toured with The Rolling Stones, the audience would come up to me after the show and say, “Man, you’re really good, you ought to record.” How do you think that makes me feel after 25 years in the business?’

Bobby Womack, 1984

‘I find politics ruins everything. Music, films, it gets into everything and f*cks it all up. People need more sense of humour. If I ran for President, I’d give everybody Ecstasy.’

Grace Jones, 1985

‘I’m not the most gifted person in the world. When God handed out throats, I got locked out of the room.’

Joe Elliott of Def Leppard, 1988

‘I’m lazy and I don’t practice guitar and piano because I’ve gotten involved with so many other things in my life and I just had to make a sacrifice. Stephen Sondheim encourages me to start playing the piano again. Maybe I will.’

Madonna, 1989

‘Nile (Rodgers) couldn’t afford to spend much time with me. I was slotted in between two Madonna singles! She kept coming in, saying “How’s it going with Nile? When’s he gonna be free?” I said, “He ain’t gonna be free until I’m finished! Piss off!”’

Jeff Beck, 1989

‘I’ve never really understood Madonna’s popularity. But I’ve talked to my brothers and they all want to sleep with her, so she must have something.’

Nick Kamen, 1987

‘They ask you about being a Woman In Rock. The more you think about, the more you have to prove that you’re a Woman In Rock. But if you’re honest, it doesn’t matter whether you’re male or female. That’s the way we work.’

Wendy Melvoin, 1989

‘In Japan, someone told me I was playing punk saxophone. I said, “Call me what you want, just pay me”.’

George Adams, 1985

‘In the past, we’d bump into other musicians and it would be, “Oh, yes, haven’t I heard of you lot? Aren’t you the bass player that does that stuff with your thumb?” But once you’ve knocked them off the number 1 spot in Germany, they’re ringing you up in your hotel and saying, “Hey, howyadoin’? We must get together…”‘

Mark King of Level 42, 1987

‘We played London, we played Ronnie Scott’s, and I noticed that there were a lot punk-rock kids in the audience. After we finished playing, we had to go to the disco and sign autographs, because “Ping Pong”, the thing we made about 30 years ago, is a big hit over there.’

Art Blakey, 1985

‘I believe music – just about everything – sounds better these days. Even a car crash sounds better!’

Miles Davis, 1986

‘It’s a dangerous time for songwriters in that a monkey can make a thing sound good now.’

Randy Newman, 1988

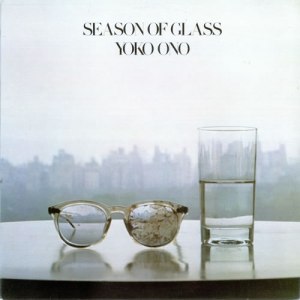

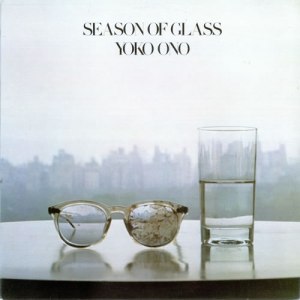

‘To have those glasses on the cover was important because it was a statement and you have to understand that it was like John wanted you guys to see those glasses.’

Yoko Ono, 1989

‘I’ll f*cking… I’ll go and take on anyone, any white singer who wants to give me a go.’

Matt Goss of Bros, 1989

‘I’ve never said this before but my drums is so professional, man, know what I mean?’

Luke Goss of Bros, 1989

‘I hate parts of my own albums because I know I’m hearing something that doesn’t translate to piano. In fact, I’m being dishonest by playing piano at all.’

Keith Jarrett, 1987

‘When I began to see how Elvis lived, I got such a strong take off of it. It was all so revolting!’

Albert Goldman, 1988

‘The best way to make great art is to have it trivialised by other people as much as possible. That way, you fight and fight and fight.’

Julian Cope, 1989

‘Whatever you’re tops in, people is trying to bring you down, and that’s my philosophy.’

Samantha Fox, 1987

‘Call me fat and I’ll rip your spine out.’

Ian Gillan, 1983

‘Sure I care about my fans. Because fans is money, hahaha. Muh-neee! And who does not care about money? Me, I like muh-neee, haha.’

Chuck Berry, 1988

‘I have this long chain with a ball of middle-classness at the end of it which keeps holding me back and that I keep sort of trying to fight through. I keep trying to find the Duchamp in me.’

David Bowie, 1980

‘People who say, Oh, I don’t know anything about music – they’re the people who really do know about music because it’s only really what it does to you.’

Steve Winwood, 1988

‘I notice that critics and others don’t credit black people with the ability to write ingenious, creative lyrics.’

Nile Rodgers, 1981

‘I’m below the poverty line – I’m on £16 a week. We needed some clothes and our manager said, “I don’t know what you do with your money. I mean, 16 quid!”’

Gary Daly of China Crisis, 1984

‘You take four or five of those rattlesnakes, dry ’em out and put them inside your hollow-box guitar. Lightnin’ Hopkins taught me that trick.’

Albert Collins on his guitar tone, 1988

‘People are bored with Lionel Richie going “I love everybody, peace on earth, we are the world…” F*ck that! People love bastards.’

Terence Trent D’Arby, 1987

‘Epstein dressed The Beatles up as much as he could but you couldn’t take away the fact that they were working-class guys. And they were smart-arses. You took one look at Lennon and you knew he thought the whole thing was a joke.’

Billy Joel, 1987

‘I remember when the guy from Echo & The Bunnymen said I should be given National Service. F*** him...’

Boy George, 1987

‘No-one should care if the Rolling Stones have broken up, should they? People seem to demand that I keep their youthful memories intact in a glass case specifically for them and damn the sacrifices I have to make. Why should I live in the past just for their petty satisfaction?’

Mick Jagger, 1987

‘The industry is just rife with with jealousy and hatred. Everybody in it is a failed bassist.’

Morrissey, 1985

‘I couldn’t stand it – all that exploitation and posturing, the gasping at the mention of your name, the pursuit by photographers and phenomenon-seekers. You get that shot of adrenalin and it’s fight or flight. I chose flight many a time.’

Joni Mitchell, 1988

‘I’m strongly anti-war but defence of hearth and home? Sure, I’ll stick up for that… I’m not a total pacifist, you know? I’ve shot at people. I missed, but I shot at them. I’m sort of glad I missed…’

David Crosby, 1989

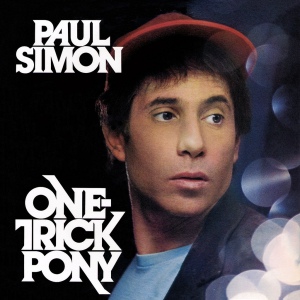

By his own admission, Paul Simon had some very lean years between his 1975 classic Still Crazy After All These Years and 1986’s multi-million selling, multi-Grammy-winning Graceland.

By his own admission, Paul Simon had some very lean years between his 1975 classic Still Crazy After All These Years and 1986’s multi-million selling, multi-Grammy-winning Graceland.

Watching the superb reruns of ‘Top Of The Pops’ recently, it’s apparent how many great bass players stormed the UK charts during the early/mid-’80s.

Watching the superb reruns of ‘Top Of The Pops’ recently, it’s apparent how many great bass players stormed the UK charts during the early/mid-’80s.