Speedily recorded 40 years ago this autumn at Newcastle’s Lynx Studios, Protest Songs was intended to be the no-frills, lo-fi, rush-released, ‘answer’ album to Prefab’s Steve McQueen.

Speedily recorded 40 years ago this autumn at Newcastle’s Lynx Studios, Protest Songs was intended to be the no-frills, lo-fi, rush-released, ‘answer’ album to Prefab’s Steve McQueen.

Fans who attended the Two Wheels Good UK tour of October and November 1985 were given leaflets advertising its release on 2 December for one week only.

But then ‘When Love Breaks Down’ reached #25 at the third attempt, earning the band spots on ‘Top Of The Pops’ and ‘Wogan’, and the album was shelved (though apparently a few hundred white labels ‘escaped’ from CBS and are out there somewhere…)

Protest Songs was eventually held back until June 1989, but proved well worth the wait and reached a respectable #18 on the UK chart. This writer would put it right up there with Steve, From Langley Park To Memphis and Jordan, maybe even above them…

The album was produced by the band and – apart from the last-minute addition ‘Life Of Surprises’ – mixed by Richard Digby Smith, once a staff engineer at Island Records who served his apprenticeship under the likes of Arif Mardin, Phil Spector, Muff Winwood and Chris Blackwell.

Protest also showed that Patrick Joseph McAloon was turning into a really decent keyboard player (he later claimed that every song on Langley Park was written on keyboards) and that – massively helped by drummer Neil Conti – Prefab were becoming a really good live band.

But most importantly Protest is a moving, razor-sharp suite of songs. Paddy was operating at the absolute top of his game, with some of the anger which had initially been so attractive to Thomas Dolby (also detectable in this recently discovered interview).

The only thing tongue-in-cheek about it is its title. These were not protests against nuclear power or war, but rather against deprivation and, just six months on from the miners’ strike, the general media condescension about provincial English life (particularly in the McAloon brothers’ native North East) under Thatcher.

‘Til The Cows Come Home’ may be the killer track. If you’re in the mood, it can be a real heartbreaker. The superb lyrics deftly change perspective mid-thought and allude to how unemployment affects generations:

Aren’t you a skinny kid?

Just like his poppa

Where’s he workin’?

He’s not workin’…

Why’re you laughin’?

You call that laughin’?

Wearing your death head grin

Even the fishes are thin…

He can’t have his coffee with cream

Meanwhile ‘Diana’ was revamped from the ‘When Love Breaks Down’ B-side (Deacon Blue definitely listened to THAT), slowed down and with a few new chords added. Conti expertly marshals proceedings with his tasty Richie Hayward-style half-time groove.

‘Dublin’ showcases Paddy’s lovely sense of chord movement, with a little influence from bossa nova (here’s Paddy playing a different studio take). ‘Life Of Surprises’ and ‘The World Awake’ are shiny, synth-laden, mid-period 4/4 Prefab but with stings in their tails:

Never say you’re bitter, Jack

Bitter makes the worst things come back

You don’t have to pretend you’re not cryin’

When it’s even in the way that you’re walkin’…

The hilarious ‘Horsechimes’ investigates school-day piss-taking, with a large dollop of Salingeresque satire. Meanwhile it’s hard to think of a more perfect marriage of words and melody than ‘Talking Scarlet’ (also drastically slowed down from the early demo), while ‘Pearly Gates’ closes out the album in moving style, like a dimly-remembered hymn from school days, a rare 1980s ‘death disc’.

The only partial misfire is the jaunty ‘Tiffany’s’, with its comically poor guitar solos, but its inclusion was totally understandable. Happy birthday to a classic.

Bryan Ferry’s one and only UK #1 album to date (and biggest-selling record in the US) was released 40 years ago this month.

Bryan Ferry’s one and only UK #1 album to date (and biggest-selling record in the US) was released 40 years ago this month.  Quentin Tarantino recently drew an interesting comparison between the 1980s careers of Chevy Chase and Bill Murray.

Quentin Tarantino recently drew an interesting comparison between the 1980s careers of Chevy Chase and Bill Murray. Fripp’s debut solo album, originally recorded at New York’s Hit Factory between January 1978 and January 1979, has endured endless tinkering from the artist including various remixes/reversions.

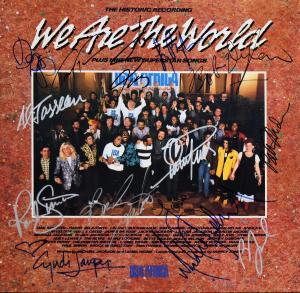

Fripp’s debut solo album, originally recorded at New York’s Hit Factory between January 1978 and January 1979, has endured endless tinkering from the artist including various remixes/reversions. Released 40 years ago this month and officially the fastest-selling single in American music history, USA For Africa’s ‘We Are The World’ shifted over 20 million copies and raised a huge amount of money for African famine relief.

Released 40 years ago this month and officially the fastest-selling single in American music history, USA For Africa’s ‘We Are The World’ shifted over 20 million copies and raised a huge amount of money for African famine relief.