Simon Booth, Juliet Roberts and Larry Stabbins of Working Week

I’ve just had the pleasure of writing the liner notes to a really good new live album by Working Week, possibly the premier jazz/pop band of the 1980s.

It got me thinking about why jazz has totally disappeared from the charts and why the first half of the ’80s seemed the perfect time for jazz and pop to co-exist, especially in the UK.

Here an excerpt from the notes:

‘Does jazz go into pop? Judging by the current music scene, the answer would appear to be an unequivocal ‘no’, but, for a golden period in the early-to-mid ’80s, it seemed as if the two styles could happily co-exist.

Artists like David Sylvian, John Martyn, Hue and Cry, Elvis Costello, Kate Bush, The Rolling Stones, Sting, Danny Wilson, Swing Out Sister, Joe Jackson and Everything But The Girl smuggled some cool chords into the charts introduced the pop audience to players of the calibre of Kenny Wheeler, Harry Beckett, Lester Bowie, Michael Brecker, Ronnie Scott, Eberhard Weber, Sonny Rollins, Guy Barker, Kenny Kirkland and Branford Marsalis.

Sade, Carmel, The Style Council and Matt Bianco’s fusion of jazz and pop wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea but all of them had big hits. The Stranglers’ ‘Golden Brown’ was a jazz waltz (with a few bars of 4/4 thrown in) which got to number one!

The advertising and TV industries played ball and a full-scale jazz ‘revival’ was underway, documented in classic 1986 documentary ’10 Days That Shook Soho’. Courtney Pine and Miles Davis shared space on the UK album chart, Wynton Marsalis made the cover of Time and you could even catch Loose Tubes, Tommy Chase and Andy Sheppard on primetime terrestrial TV.

DJs Paul Murphy, Baz Fe Jazz, Patrick Forge and Gilles Peterson packed out Camden’s Dingwalls and the Electric Ballroom and young hepcats were dancing to Cannonball Adderley, Roy Ayers, Donald Byrd, Art Blakey and Lee Morgan.

Dancers at Dingwalls, London, 1988

Though older British jazzers such as Stan Tracey, Keith Tippett and Mike Westbrook (and some younger ones too) naturally viewed this latest revival with some suspicion, at least it was a relief from the extremely precarious ’70s when rock, funk and fusion almost subsumed jazz.

The old guard hung on, gigging in the back rooms of pubs, picking up occasional free improve shows in Europe or moonlighting in West End pit orchestras. But then punk came along, and it affected more than just disenfranchised young rock fans – its DIY ethos breathed new life into jazz too. Bands like Rip Rig + Panic and Pigbag made huge strides in engaging a youthful, receptive audience. Pigbag even made it onto ‘Top Of The Pops’…twice!

But it was Working Week, co-founded in 1983 by saxophonist Larry Stabbins and guitarist Simon Booth, who really typified the successful fusion of jazz and pop in mid-‘80s. Formed in 1983 from the ashes of jazz/post-punk outfit Weekend (whose ‘The View From Her Room‘ was a confirmed early-’80s club classic), initially Working Week was almost the de facto house band for the emerging scene, with the infectiously exuberant IDJ dancers often joining them onstage.

Robert Wyatt and Tracey Thorn duetted on classic single ‘Venceremos – We Will Win’ which briefly made an appearance on the UK singles chart in late 1984. The accompanying album Working Nights, featuring other Brit jazz legends Guy Barker, Harry Beckett and Annie Whitehead and produced by Sade’s regular helmer Robin Millar, reached a sprightly number 23 in the UK album chart soon after…’

Read more in the Working Week live album.

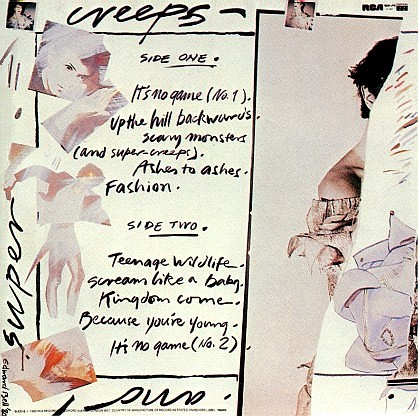

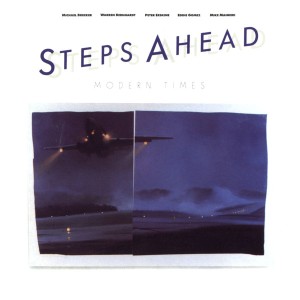

It’s fair to say that the 1980s spawned more than a few overproduced records.

It’s fair to say that the 1980s spawned more than a few overproduced records.

Like a lot of music fans, I can’t resist a list, so here are my top 15 albums as of today.

Like a lot of music fans, I can’t resist a list, so here are my top 15 albums as of today.

It all came back to me recently when I heard some church bells in Totnes ringing out the opening bass melody from ‘We Could Send Letters’.

It all came back to me recently when I heard some church bells in Totnes ringing out the opening bass melody from ‘We Could Send Letters’.