On 17 April 1985, just ten days after the end of the Purple Rain tour, Prince walked into LA’s Sunset Sound studios, sat at the drums, taped the lyrics of four new songs onto a music stand, picked up his sticks and instructed engineer Susan Rogers: ‘Don’t stop the tape when I stop playing. Just keep rolling.’

On 17 April 1985, just ten days after the end of the Purple Rain tour, Prince walked into LA’s Sunset Sound studios, sat at the drums, taped the lyrics of four new songs onto a music stand, picked up his sticks and instructed engineer Susan Rogers: ‘Don’t stop the tape when I stop playing. Just keep rolling.’

He then played through ‘Christopher Tracy’s Parade’, ‘New Position’, ‘I Wonder U’ and ‘Under The Cherry Moon’ without pausing. This guy worked fast. The recording sessions for Parade had begun.

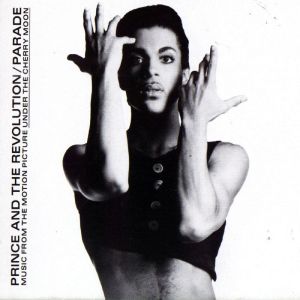

The album would see Prince continue his extraordinary mid-’80s run of form, surely comparable to Stevie Wonder’s fabled 1972–1976 period. He couldn’t release albums fast enough and the wider world was waking up to just how prolific he really was.

His striking new horns-and-orchestra-driven sound, by turns jazzy, funky and psychedelic, lost him some fans in the States but made him a huge star in Europe. Parade showed off the amazing versatility of Prince (drums, bass, guitar and keyboards) and his main collaborators Wendy (guitar) & Lisa (keyboards).

It’s an anti-boredom album full of glorious contradictions – it features his first instrumental track but still contains four classic dancefloor singles; it’s his densest, most ‘produced’ ’80s album (alongside Lovesexy) and yet features his first all-acoustic track, recorded completely live in the studio; Clare Fischer’s orchestral arrangements are always high in the mix but rub shoulders with the Sunset Sound’s ancient sound effects library; Prince utilises ultramodern tech like a guitar synth and a Fairlight sampler, but the main solo instruments are Eric Leeds’ tenor and baritone sax. And there is zero electric lead guitar, barely 18 months after Purple Rain.

References this time around were The Beatles, ’80s Miles Davis, show tunes and funk-era James Brown. The biggest influence though is late-’70s Joni Mitchell. Parade is the nearest Prince ever got to the kaleidoscope range of her classic albums Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Hissing Of The Summer Lawns.

There were also more vocals in Prince’s music than ever before: Wendy, Lisa, Susannah (Wendy’s sister and Prince’s fiancée) and Sheila E all contributed massively to the occasional West Coast/Bangles sound.

By 2 June 1985, nine songs for Parade were in the can, though three would later be left off the final album – the spooky ‘Others Here With Us’, fantastic ‘All My Dreams’ and superfunky ‘Sexual Suicide’. Prince was also now working on not one but two other albums, Jill Jones and Mazarati’s debuts. By late June, he was also scouting locations in the south of France for the upcoming ‘Under The Cherry Moon’ movie. But, true to form, he couldn’t stop recording – he set up a makeshift recording studio in his Antibes hotel suite.

Parade‘s first three tracks – ‘Christopher Tracy’s Parade’, ‘New Position’ and ‘I Wonder U’ – pass by in the blink of an eye, gloriously odd, genuinely psychedelic funk miniatures. Very few have taken on the mantle of this style of music since 1986, though D’Angelo had a good go on the superb Voodoo album.

‘Under The Cherry Moon’ is almost a ’30s-style jazz number featuring asthmatic synths, fantastic piano playing and a daring melody line. I’d like to hear Tom Waits’ cover. If you listen very closely, you can hear the rattle of Prince’s necklace as he lays down the drum track.

‘Girls And Boys’ is a classic one-chord funk tune whose blaring guitar synth adds an engaging weirdness. Saxophonist Eric Leeds makes his mark on Prince’s music for the first time (though had already featured prominently on The Family’s album).

‘Life Can Be So Nice’ features fake harpsichord, sampled flute, piercing cowbell, some intricate acoustic guitar and a heavily-treated kick drum. It’s discordant and thrilling with an envelope-pushing vocal arrangement and some bizarre lyrics. The last minute of the song is a Latin/fusion jam in the Santana or Weather Report vein.

‘Venus De Milo’ is a sumptuous piece of symphonic muzak with some gorgeous trumpet from Matt Blistan (renamed Atlanta Bliss by Prince) while ‘Mountains’ is another classic single, largely penned by Wendy & Lisa. The 12” mix has to be heard. ‘Do U Lie’ is an intoxicating little slice of soft jazz with cocktail guitar, spoken word, strings and accordion.

‘Kiss’ is another effortless classic. It was the first single to be released from Parade, hitting US number one in April ’86, though apparently loathed by the Warner Bros suits. Initially given to the band Mazarati for their debut album, it was reclaimed by Prince when he realised the potential of the track. He kept their backing vocals and gave them some money.

‘Anotherloverholenyohead’, recorded on 16 December 1985, was the last track recorded for Parade. Lisa’s crystalline, densely-voiced piano sounds like it was recorded in a school assembly hall, and there’s more peculiar guitar synth and a few incredible bass runs from Prince. The full-length version made for another classic 12” single. Album-closer ‘Sometimes It Snows In April’ is Joni all the way. Its improvised, rubato prologue is very reminiscent of the opening to Mitchell’s ‘Cotton Avenue’.

Prince delivers an amazing lead vocal but the song needs a stronger chorus (‘Sometimes I feel so bad’) and Wendy & Lisa’s backing vox are extremely rough. The track divides opinion – some find it moving, some mawkish (I’m in the latter camp) – but it was a pretty brave choice to close such an important album.

The Parade sessions also spawned some fantastic B-sides: ‘Alexa De Paris’, ‘Sexual Suicide’, ‘Power Fantastic’, ‘4 The Tears In Your Eyes’, ‘Love Or Money’, ‘All My Dreams’ and the notorious ‘Old Friends 4 Sale’. All are well worth seeking out. Despite the success of ‘Kiss’ in the States, three follow-up singles peaked outside the top 50. Prince believed that Warner Bros’ choice of second single (‘Mountains’) was wrong – it should have been ‘Girls And Boys’.

Parade sold considerably less (1.8 million) in the States than Purple Rain (10 million) and Around The World In A Day (4 million). But in Europe, it was a huge hit. Then came the European tour. A funk revue. Horns, dance routines, backing vocals. Again, virtually no lead guitar. Europe loved him – there were riots in Holland – but the tour didn’t even make the States, which many insiders believe was a big mistake. Instead, there were several separate shows under the banner of the Hit & Run Tour.

But then it was all change: Wendy & Lisa were out of the band, Prince and Susannah had broken off their engagement and ‘Under The Cherry Moon’ had stiffed. But there were still a couple of amazing albums left in the tank before Prince’s ’80s were out.

During a 1981 interview, Peter Gabriel said: ‘Many great songs have really appalling lyrics, but no great songs have had appalling music. If you’re going to write lyrics, you might as well make them try and communicate something.’

During a 1981 interview, Peter Gabriel said: ‘Many great songs have really appalling lyrics, but no great songs have had appalling music. If you’re going to write lyrics, you might as well make them try and communicate something.’  When I think of ’80s Eddie Van Halen, the image in my mind’s eye is probably not a lot different to any other fan – he’s grinning from ear to ear, cavorting around the stage, playing some of the greatest rock guitar of all time with one of the sweetest tones.

When I think of ’80s Eddie Van Halen, the image in my mind’s eye is probably not a lot different to any other fan – he’s grinning from ear to ear, cavorting around the stage, playing some of the greatest rock guitar of all time with one of the sweetest tones.

One of the nice things about putting together this website is finding out about some important – though often unsung – characters who pop up in the credits of many a classic album.

One of the nice things about putting together this website is finding out about some important – though often unsung – characters who pop up in the credits of many a classic album.  Musicians gave good quote in the ’80s.

Musicians gave good quote in the ’80s.  The 1980s are littered with Brit pop bands going ‘across the pond’ to work with US producers and musicians.

The 1980s are littered with Brit pop bands going ‘across the pond’ to work with US producers and musicians.