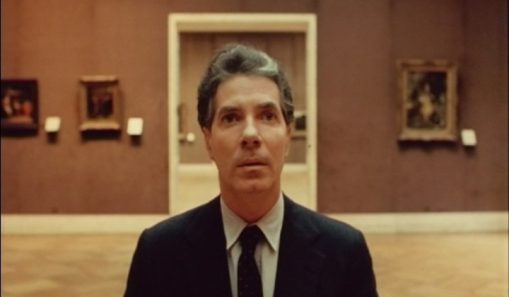

My dad was a huge Alfred Hitchcock fan.

My dad was a huge Alfred Hitchcock fan.

He liked the ‘minor’ Hitch as much as the ‘major’ Hitch. As a war baby, maybe he relished the director’s trademark mixture of dread and humour. Dad certainly didn’t sneer at ‘Psycho’; in fact, he would have put it firmly in the ‘major’ category.

We probably first watched the film together sometime around 1989. Revisiting it again recently, it struck me as a curiously – and defiantly – ‘modern’ movie.

Even as the ghastliness of America’s modern serial killers was becoming public knowledge towards the end of the 1950s, the kind of seediness ‘Psycho’ portrayed had still not been shown on screen (though David Thomson’s superb book ‘The Moment Of Psycho’ notes that a few figures – James Dean, Jerry Lewis, Elvis, Brando and Jack Nicholson, by way of Roger Corman, were ushering in a new, youthful edginess. Thomson also asks us to imagine Elvis as Norman Bates…).

Hitchcock and screenwriter Joseph Stefano really decided to let American audiences have it with their fairly loyal interpretation of Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel. Thomson describes the film as Hitch’s ‘revenge’ on Hollywood, a Hollywood that had never granted the director an Oscar and whose mixture of humour and dread had never been fully accepted.

These factors also particularly struck me when revisiting ‘Psycho’:

7. Hitchcock/Stefano’s skewering of America’s sacred cows

The family unit, marriage, the home, sanity, the bathroom (never before in an American film had there been the shot of a toilet flushing), heterosexuality, the shower stall. And the way he gleefully starts the movie tracking into a fairly seedy motel room to eavesdrop on a post-coital tryst. It all seems run-of-the-mill now but all of this must have been an incredible shock for contemporary audiences. Hitch wanted to show how modern, urban people were living their lives.

6. Joseph Stefano’s dialogue

Speed-reading Robert Bloch’s novel again, it struck me that screenwriter Stefano deserves huge praise for reworking the dialogue. He puts some pep in its step, fashions some brilliant lines for Norman (the whole mental illness speech during dinner with Marion in his den) and turns the scenes between Norman/Sam Loomis (John Gavin) and Norman/Arbogast (Martin Balsam) into mini masterpieces. He also adds some good, hip stuff featuring the traffic cop (who doesn’t feature in the novel) and car salesman (who does).

5. The shower murder

Hitchcock’s ‘pride’ at the slickness of the first murder scene belies its brutality. If there’s a more shocking death in the movies, I haven’t seen it. A troubling thought: to what extent does Hitchcock/Norman/’Mother’/Bloch/the audience ‘punish’ Marion for stealing (even though at the time of her murder she has made the decision to return the money)? But of course modern audiences would be primed for Janet Leigh’s early exit, since the opening credits say ‘…And Janet Leigh as Marion Crane’. It’s clear now she’s not going to last the whole movie, but audiences in 1960 wouldn’t have twigged.

4. The sexual politics of the first 40 minutes

Marion strikes us as an incredibly ‘modern’ character, strong, determined, troubled, independent, defiantly single (though willing to give Sam a try… Or is she? Why doesn’t she ring him to tell him she’s on her way with the money?). She passes through the first half of the film encountering men in scenes that somehow ‘mirror’ each other – her lover, the creepy, predatory client at work, traffic cop, car salesman, and finally Norman.

3. The concept of ‘doubles’

Of course, Norman ‘is’ Norma Bates, mother and son combined. Then there are the – on first viewing – strange matching shots of characters leaving rooms; first Marion, then ‘Mother’. Then there’s the remarkable physical likeness between Sam Loomis (John Gavin) and Norman (who, of course, in many ways seems far more pleasantly disposed towards Marion than Sam ever is).

2. The brilliance of Anthony Perkins’ performance

Hitchcock apparently instructed Stefano to write for Perkins once the teen heart-throb had signed on very early in proceedings. The novel has Norman as an overweight, alcoholic, 40-year-old schlub, but Perkins’ leading-man looks, disarming smile and gentleness are the movie’s masterstrokes. He delivers a classic performance, possibly influenced by Dennis Weaver’s panic-stricken ‘night man’ in Orson Welles’s ‘Touch Of Evil’.

1. The flatness of the second half

Hitchcock barely seems interested in any characters other than Marion and Norman, fatally unhinging the second half of the movie. It’s pretty boring apart from the above terrific scene between Norman and Arbogast (which apparently earned lengthy applause from the crew), the Arbogast murder, the ‘Mother’ reveal in the basement and the closing Norman/Mother ‘monologue’, featuring more fantastic work from Perkins.

If this was John’s final London gig, what a way to go out.

If this was John’s final London gig, what a way to go out.

It’s sometimes forgotten how much influence Faith No More had on the ‘alternative’ rock scene.

It’s sometimes forgotten how much influence Faith No More had on the ‘alternative’ rock scene.

A major trope of ’80s or ’80s-set movies, novels and plays was the insane or morally unsound banker, broker or trader.

A major trope of ’80s or ’80s-set movies, novels and plays was the insane or morally unsound banker, broker or trader.

My Steve Martin ‘thing’ probably peaked around 1989.

My Steve Martin ‘thing’ probably peaked around 1989.