Any British music fan who came of age during the 1980s must surely have a soft spot for The Face magazine.

Any British music fan who came of age during the 1980s must surely have a soft spot for The Face magazine.

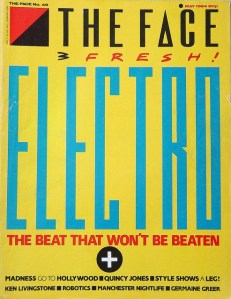

Launched by Smash Hits founder/NME editor Nick Logan in May 1980, the monthly rag – so named because of its Mod allegiances – quickly become known as a first-rate style mag (it covered fashion, music, culture, clubbing and cinema too), with its many famous covers reaching the level of high-quality pop art.

Indeed, looking again at issue #1, it’s remarkable how many of its listed writers and photographers would turn out to be key documentors of the decade – Janette Beckman, Julie Burchill, Gary Crowley, Anton Corbijn, Ian Cranna, Jill Furmanovsky, David Hepworth, Tony Parsons, Sheila Rock, Pennie Smith (and that issue alone features iconic photos of Madness, The Specials, The Clash, John Lydon and Paul Weller, amongst others).

It was also unique amongst 1980s music mags in paying as much attention to reggae, hip-hop, electro, house, rare groove and jazz as it did to post-punk, 2-Tone and sophistipop.

But movingtheriver also remembers it most for its superb long-form interviews: I still have issues featuring in-depth pieces on Miles Davis, Trouble Funk, Dennis Hopper, David Sylvian, David Byrne, Robert Smith, Daryl Hall and Ken Russell.

The Face’s iconic imagery is celebrated at the excellent if compact new exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery. Predictably it’s photos from those post-punk/New Pop salad days of 1980-1983 which produce the most smiles of recognition/pleasure – Bowie in Japan, Adam Ant, Phil Oakey, John Lydon, Annie Lennox.

But there are great pics/stories from later in the decade too – Bros with their mum at home in Peckham, Shane MacGowan, Sade, Nick Kamen, Felix et al. There’s also a great chronology of 1980s clubbing, from Goth to Acid House, and a focus on long- lost London nightspots.

As the 1980s became the 1990s, The Face arguably reflected a gradual coarsening of the culture with more focus on fashion and lifestyle – but you knew that anyway. But this exhibition is a must-see for any music fan who loved the 1980s, and it was also refreshing to see such a broad range of ages attending.

The Face Magazine: Culture Shift runs at the National Portrait Gallery until 18 May 2025.

It was one of the many issues that probably had managers and marketing people tearing their hair out during the 1980s.

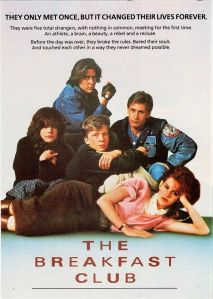

It was one of the many issues that probably had managers and marketing people tearing their hair out during the 1980s. Despite a few bum notes, ‘The Breakfast Club’ – which premiered 40 years ago this month – remains one of the essential 1980s movies, a must-see for generation after generation of teenagers.

Despite a few bum notes, ‘The Breakfast Club’ – which premiered 40 years ago this month – remains one of the essential 1980s movies, a must-see for generation after generation of teenagers.  Look up ‘intense’ in the dictionary and you might just see a photo of Jaz Coleman.

Look up ‘intense’ in the dictionary and you might just see a photo of Jaz Coleman. In 1986, legendary mag NME issued a famous cassette compilation called C86.

In 1986, legendary mag NME issued a famous cassette compilation called C86.  There’s a good case that 1984 was Last Call for classic jazz/funk (soon to morph into the dreaded smooth jazz) just before the machines took over and albums like David Sanborn’s A Change Of Heart became de rigeur (but only for a few years – there was an ‘acoustic’ revival in the late 1980s…).

There’s a good case that 1984 was Last Call for classic jazz/funk (soon to morph into the dreaded smooth jazz) just before the machines took over and albums like David Sanborn’s A Change Of Heart became de rigeur (but only for a few years – there was an ‘acoustic’ revival in the late 1980s…). It’s one of the great mysteries of pop culture, up there with who buys The Wire magazine and who goes to Snow Patrol gigs – why wasn’t comedian/actor John Sessions a bigger star (born John Marshall, he sadly died in 2020)?

It’s one of the great mysteries of pop culture, up there with who buys The Wire magazine and who goes to Snow Patrol gigs – why wasn’t comedian/actor John Sessions a bigger star (born John Marshall, he sadly died in 2020)? One of the unexpected treats of last year was a new – and excellent – album from the Sun Ra Arkestra: Lights On A Satellite.

One of the unexpected treats of last year was a new – and excellent – album from the Sun Ra Arkestra: Lights On A Satellite. Marlena Shaw (pictured left)

Marlena Shaw (pictured left) You should never judge a person by their name.

You should never judge a person by their name.