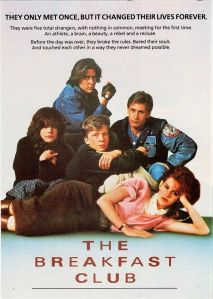

Despite a few bum notes, ‘The Breakfast Club’ – which premiered 40 years ago this month – remains one of the essential 1980s movies, a must-see for generation after generation of teenagers.

Despite a few bum notes, ‘The Breakfast Club’ – which premiered 40 years ago this month – remains one of the essential 1980s movies, a must-see for generation after generation of teenagers.

Like or loathe it (some contemporary critics such as Pauline Kael lamented its whinier aspects, while others such as Roger Ebert were surprisingly sympathetic), its superb cast act as if their lives depended on it, and writer/director John Hughes’s attention to detail and comic timing are as spot-on today as they must have seemed in 1985.

But what was going on behind the scenes? Where was the film shot? Which famous actors nearly got cast? Which actors didn’t get along? Movingtheriver has done some digging (with spoilers)…

17. The film was edited by Hollywood royalty Dede Allen, who had worked on ‘The Hustler’, ‘Bonnie & Clyde’, ‘Serpico’, ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ and ‘Reds’ (apparently she was put to work on John Hughes’ original three-hour cut…).

16. Theme song ‘Don’t You Forget About Me’ was written by Keith Forsey after witnessing the scene where Brian (Anthony Michael Hall) asks his fellow detention attendees if they’ll still be friends the next day. Simple Minds turned it into a US #1 but Bryan Ferry was Forsey and Hughes’ first choice – he turned it down, busy mixing Boys & Girls.

15. Hughes wrote the first draft of the film over one weekend.

14. Universal weren’t behind the film, wanting more teenage hi-jinks and nudity a la ‘Porky’s’. They weren’t even sure Hughes should direct.

13. Anthony Michael Hall and Molly Ringwald were just 16 years old during filming – all the other ‘schoolkids’ were well into their 20s.

12. Jodie Foster, Laura Dern and Robin Wright all auditioned for the part of Claire, the prom queen. Molly Ringwald got the role despite initially being cast as Alison, the misfit. Emilio Estevez was initially cast as the ‘bully’ John Bender until Judd Nelson came in at the last minute (Nicolas Cage, John Cusack and Jim Carrey all almost played Bender too). Rick Moranis was due to play Carl the janitor but left the film just before shooting.

11. It was shot between March-May 1984 at Maine North High School in Des Plaines, Illinois, the same abandoned school used for ‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off’. Most of the film takes place in a library – this was actually a set built in the school gymnasium.

10. The cast rehearsed for three weeks before the cameras rolled. They were running lines and bonding even as sets were being built around them. The film was also shot in sequence, a rarity.

9. Researching his role as Bender, Judd Nelson went ‘undercover’ at a nearby high school with fake ID and formed a real clique of naughty teens.

8. The cast didn’t smoke real pot in the famous ‘truth-telling’ scene – it was oregano.

7. Anthony Michael Hall’s real life mother and sister talk to him in the car at the beginning (and Hughes has a cameo as his dad).

6. Ringwald tried to get Hughes to remove the scene where Bender hides under the desk and looks between her legs, but he refused.

5. Bender’s famous, defiant/celebratory fist-raise at the end was improvised by Judd Nelson.

4. The scene where the characters sit around and explain why they are in detention was all improvised.

3. The original cut was 150 minutes long – they had to lose 53 minutes, including a long dream sequence and a whole character (a sexy gym teacher). Some deleted scenes have appeared on DVDs and on YouTube but many outtakes have never been seen.

2. The iconic poster photo was taken by Annie Leibovitz and later satirised by ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2’.

1. The budget was just under $1 million! The film made over $51 million during its initial run…

Look up ‘intense’ in the dictionary and you might just see a photo of Jaz Coleman.

Look up ‘intense’ in the dictionary and you might just see a photo of Jaz Coleman. There’s a good case that 1984 was Last Call for classic jazz/funk (soon to morph into the dreaded smooth jazz) just before the machines took over and albums like David Sanborn’s A Change Of Heart became de rigeur (but only for a few years – there was an ‘acoustic’ revival in the late 1980s…).

There’s a good case that 1984 was Last Call for classic jazz/funk (soon to morph into the dreaded smooth jazz) just before the machines took over and albums like David Sanborn’s A Change Of Heart became de rigeur (but only for a few years – there was an ‘acoustic’ revival in the late 1980s…). What a treat to see that Freeview channel London Live seems to be re-running Keith Floyd’s classic BBC films of the 1980s.

What a treat to see that Freeview channel London Live seems to be re-running Keith Floyd’s classic BBC films of the 1980s.

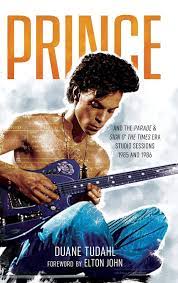

1985 was a mixed year for DB.

1985 was a mixed year for DB.  They say you should never meet your heroes – if the summer of 1985 is anything to go by, Thomas Dolby probably knows a thing or two about that.

They say you should never meet your heroes – if the summer of 1985 is anything to go by, Thomas Dolby probably knows a thing or two about that.